Published July 29, 2021 at 10:10pm.

Story and photos by Jan Osborn.

If you or someone you know is experiencing a mental health crisis or suicidal thoughts, please dial 1-800-273-8255 for the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline. For help finding a mental health resource, call the Here for Texas Mental Health Navigation Line at 972-525-8181.

As you walk down the halls of the Grant Halliburton Foundation, you are surrounded by artwork. At first glance, the bright colors and whimsical drawings appear to be created by an artist with a zest for life. The artist, Grant Halliburton, did indeed have a zest for life. He also suffered from bipolar disorder which eventually took his young life. After his death, Grant’s mother, Vanita, found the courage to share his talents with the world and help others learn to recognize the signs of mental illness.

Vanita Halliburton co-founded the Grant Halliburton Foundation (GHF) in January 2006 after her son Grant died by suicide. By sharing Grant’s story, the foundation bearing his name is creating opportunities for education around mental health in our community and helping families avoid the tragedy that Vanita experienced.

Vanita grew up in Memphis, Tennessee, calling it her hometown. She graduated from Memphis State University with a degree in journalism while working her way through college at the local public television station. Since public television stations are usually short on budget, Vanita was asked to host her own show at the age of 21. That opportunity turned into a five-year stint, interviewing guests for the on-air magazine-style show. Learning how to speak and interview people during a live show gave Vanita a passion for stories and learning about people who hold different perspectives.

After her time in public television, Vanita took her journalism degree and worked for an ad agency for many years until her first child, Amy, was born. Vanita ended up in Dallas in the early 80’s, and her family put down roots in the area soon after Amy’s birth. Three years after Amy was born, Grant came along and the siblings were best friends, playing dress-up and drawing together. Vanita gave her kids free rein to use their imagination. In the Halliburton household it was not unusual to find all of the white cushions from the sofa on the garage floor where the kids were building things. Vanita thought that it was important to let children express themselves, fostering an environment filled with creativity.

Amy is now grown and married with two children, and has been the director of events at Grant Halliburton for more than ten years. Her brother Grant kept his artistic streak through his teenage years. Vanita tried to set him up with music lessons when he was just six years old, but he would have no part of it. By the time he was in high school, Grant would go in the back door of their house, drop his books, and head for the piano because he had something in his head and he needed to get it out onto the keyboard. Grant and his friend started a band in high school called Apollo’s Playground, in which they composed all of their own music.

Vanita felt as though she had the best of both worlds, combining motherhood and career. After Amy was born, she began freelancing in the advertising industry, an enjoyable, yet challenging job. Then after Grant died Vanita was given a new path. “It felt like God just picked me up like I was a little matchbox car and turned me around and said, you’re going to go in this direction now.,” Vanita says.

Vanita still reflects on Grant’s life, especially the initial depression diagnosis at the age of 14. “I’ll never forget the day that the school counselor called me and said, ‘I have to tell you something. Your son has been hurting and harming himself.’ I was 1000 miles away from home on a business trip,” Vanita remembers. “When I was called out of my meeting, because the school was calling. I kept talking to the woman from school, on the phone until I ended up on the front steps of this high rise, business building. When she said that we were going to need to get help for Grant, I just sat down on the curb and cried. I couldn’t believe that I didn’t know he was hurting. I couldn’t believe that he was suffering silently. He never showed any outward signs.”

Vanita now knows that this kind of mental illness is called “smiling depression” because people can be deeply suffering, but putting up a good front. “Grant was the one who wanted to help everyone else,” Vanita says. “He was the one who wanted to make others happy or keep them laughing. He was the clown. He was the entertainer. And so his depression was hidden underneath.”

Many years later Vanita learned more about what was going on in her son’s brain. After the call from the school, Grant received help from mental health professionals for the next five years.

Grant Halliburton as a teenager. Photo courtesy of Vanita Halliburton.

When he graduated from high school, Grant turned down scholarships to some of the top art schools in the country, even after touring several. Vanita remembers he told her, “I don’t want to go to college. I don’t want to do anything.”

Eventually, Grant reluctantly agreed to go to the University of Texas at Austin, where he stayed for a very short time. He came home one weekend and told Vanita that he did not think he was able to live a normal life without some serious help. Vanita knew at that moment to get on the phone and start making calls to therapists and psychiatrists just to see what they should do. Knowing that teenagers can often change their mind, Vanita reached out for help at that exact moment. Vanita said, “It was incredibly hard to find out where to go. Even the therapist couldn’t say for sure, go here or go there. We ended up going to a very reputable hospital with a psychiatric unit in Dallas, where Grant stayed for 30 days.”

During that stay, Grant was diagnosed with bipolar disorder with psychosis, a serious form of that illness. Grant stayed willingly during that time but then was ready to get home and figured out what he could tell the doctors in order to be released. As part of the release process, hospital staff reminded him to take his medication, get plenty of rest and stick to a schedule. Grant went to stay with his dad, but he was not himself. Just two weeks after leaving the hospital, Grant jumped from a 10-story building, just one block away from home in the middle of a clear November day.

“That is where our work began,” Vanita says. “We didn’t know what we needed to know. I didn’t know that the time right out of a psychiatric stay of any kind for anybody at any age, is one of the highest risk times for suicide. You are thinking that they have been getting treatment and they are better. But they either got enough treatment to feel strong enough to act on those desires or they just reached a point where they felt there was no other option.” Vanita knows that there are many reasons people die by suicide, but for Grant she thinks it was despair.

It was the following January that Vanita began wanting to frame Grant’s art and host an art show. They immersed themselves in the project that kicked off a 30-day exhibition in one gallery, hoping that Grant’s artwork would start conversations around mental health. After the first gallery showing, another gallery was interested in displaying the artwork.

But during this time, Vanita was also still deep in a season of grief, working just putting one foot in front of the other. “I don’t think it was particularly healthy,” she says. “I wasn’t deferring my grief, but I was pouring all of my energy into something just to keep me from literally drowning in it.”

The foundation was underway in 2006, but their first fundraiser took place in 2011. “Our goal was to help people know what I didn’t know,” Vanita says.

Vanita attended suicide prevention conferences and national mental health conferences, trying to learn more about the suicidal mind, how you prevent suicide, and how to recognize the warning signs, but those experiences drew painful memories to the surface. Now Grant Halliburton Foundation is focused specifically on sharing this practical type of information. “We want every parent, adult, teachers, counselors, friends, relatives in the lives of children to know what these signs look like as readily as we know the signs of an oncoming cold,” Vanita says.

Grant Halliburton Foundation now has trained over 200,000 students, parents, teachers, counselors, Girl Scouts and corporate team members. All training is done in small groups or classroom settings, strategically choosing to avoid large assemblies at schools. “There’s nobody who doesn’t need this information,” Vanita says. “Everybody needs to know this.”

One of the things that Vanita often talks about is the cost of silence and the stigma in the workplace. “We need to recognize that one in four people have symptoms of depression,” Vanita says. “That means we are working with people who are dealing with anxiety, depression, and more things. Everybody needs to know, not just the warning signs of suicide, but what a mental condition looks like and how they look different in the workplace. We are trying to educate people to be more open and educated about it. Nothing happens when the stigma is alive and well. Until the stigma is brought out of the shadows and into the light, it will thrive. So there’s a very simple premise here: Education is the beginning of knowledge. Knowledge is the beginning of getting rid of stigma, making it okay for people to talk about not being okay.”

>

“Nothing happens when the stigma is alive and well. Until the stigma is brought out of the shadows and into the light, it will thrive. So there’s a very simple premise here: Education is the beginning of knowledge. Knowledge is the beginning of getting rid of stigma, making it okay for people to talk about not being okay.”

In 2019, the Grant Halliburton Foundation opened their Mental Health Navigation Line. Vanita said, “We felt it was important that people would have a number to call and say whatever they needed to say and know that someone was listening.”

Education is the number one goal at the Grant Halliburton Foundation and the second highest goal is connecting people to resources. Vanita explained when she needed help for Grant, she didn’t know who to ask. The navigation line is monitored Monday through Friday, and is completely volunteer driven. All volunteers have 40 hours of training in mental health and empathetic listening. Volunteers are taught how to manage a call and learn the software to correctly gather all of the information input for the file. Within 24 hours the caller has been emailed a list of resources that fit their needs, insurance, ability to pay, where they live, whatever the circumstances. During COVID, the navigation line had to pivot to find a way to make the line work with the same telephone number, but with a team of 30 volunteers being able to accept calls from their homes. Vanita proudly says, “We didn’t miss a beat with the navigation line.”

Centers for Disease Control reported in 2020 that mental illness is more prevalent during times of COVID-19. Anxiety was three times more common, depression was four times more common, and suicidal thoughts were up by two times. One in ten people reported seriously considering suicide.

“We keep tossing around the term ‘finding our new normal,’” Vanita says. “I don’t know that I agree there’s a new normal. I think there is ‘a moving forward.’ We have to watch out for each other, not just children but for everybody. We have to realize the pandemic changed each of us in some way and acknowledge that we need a little help. We need to take self-care seriously because stress is very harmful to our bodies.”

Do you wonder what inspires Vanita? “The ability to share with even one parent, one adult, one teacher, one person in a corporation, anyone,” she says. “Just to share with one person, something they didn’t know before, to enrich lives letting someone know that it’s going to get better and maybe they won’t get to that point of feeling suicidal.”

If you need help finding mental health resources, call Here For Texas Mental Health Navigation Line at 972-525-8181. If you are interested in learning how to get involved as a volunteer or support GHF, visit their website.

Featured

More Good Stories

Featured

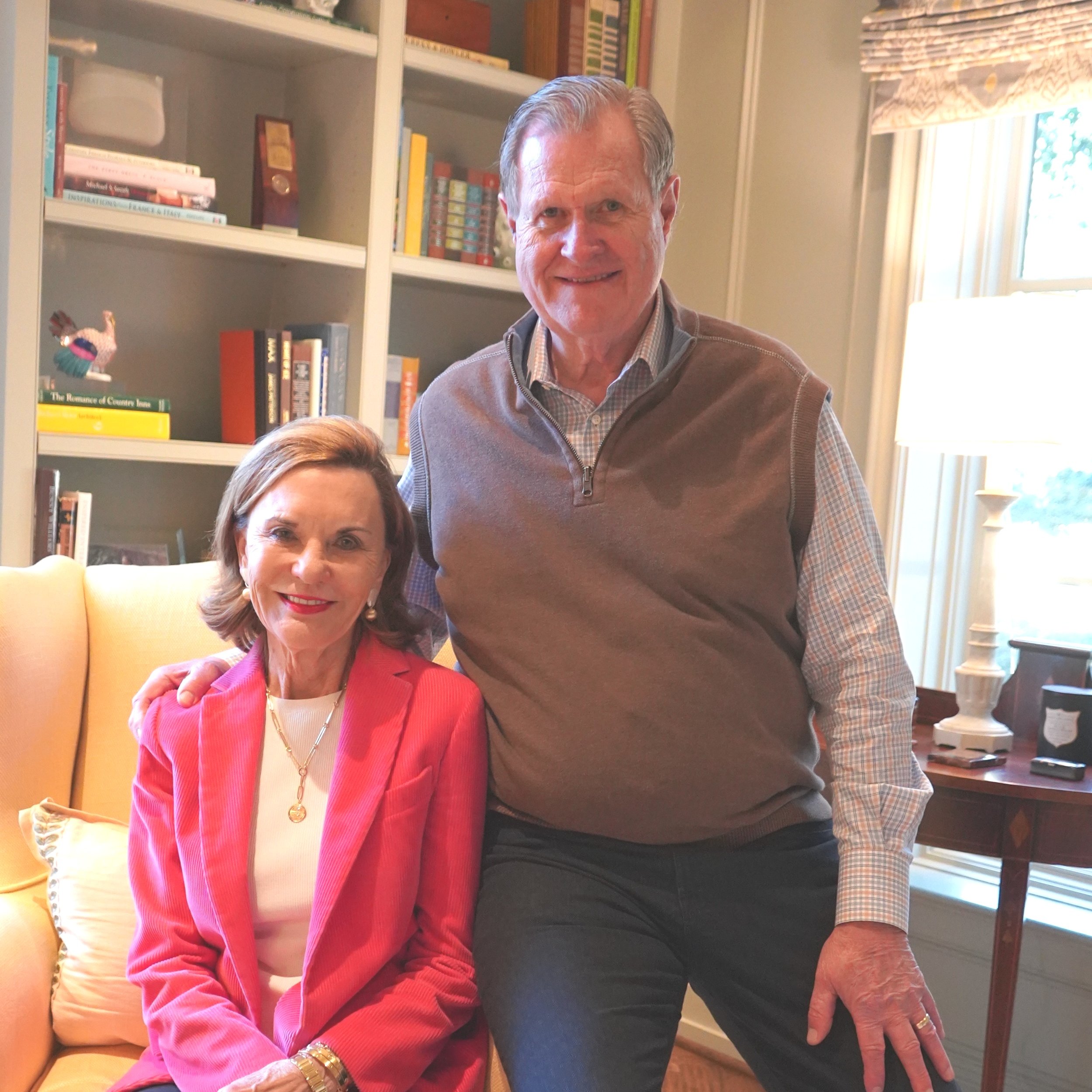

When Kathy and Larry Helm heard about The Senior Source’s 60th Birthday Diamond Dance-Off, they knew they had to put on their dancing shoes! For the Helms, this event combined two of their passions into one. Celebrating and supporting The Senior Source, a Dallas-area nonprofit that has been serving older adults for 60 years, and dancing together, which they have been doing since they were high school sweethearts. Both Kathy and Larry have chaired the board of directors of The Senior Source and have been proud supporters since 1998. It seemed only fitting they should be voted into the finals to dance on stage at Klyde Warren Park this past summer.

In 2020, more than 912,000 women were diagnosed with some form of cancer in the United States alone. During that same pandemic year, countless medical appointments were canceled while people were social distancing, and yet still each day nearly 2,500 women heard the news, “you have cancer.” There is no doubt that these words can be crushing to hear, but what’s equally crushing is the lack of tangible, encouraging support that exists to help women feel beautiful, strong or “normal” before, during and after cancer treatment.

When Tom Landis opened the doors to Howdy Homemade in 2015, he didn’t have a business plan. He had a people plan. And by creating a space where teens and adults with disabilities can find meaningful employment, he is impacting lives throughout our community and challenging business leaders to become more inclusive in their hiring practices.

Have you ever met someone with great energy and just inspired you to be a better you? Nitashia Johnson is a creator who believes by showing the love and beauty in the world it will be contagious and make an impact. She is an encourager and knows what “never give up” means. Nitashia is a multimedia artist who works in photography, video, visual arts and graphic design. Her spirit for art and teaching is abundant and the city of Dallas is fortunate to have her in the community.

The United Nations Association Dallas Chapter (DUNA) honored Rev. Bill and Norma Matthews for their ongoing commitment, helping advance the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals agenda by promoting peace and well-being.