Published March 3, 2021 at 11:19am.

Story by Mary Martin. Photos courtesy of Dexter D. Evans.

Dexter D. Evans loves writing thank you notes. Everything from the stationery to his custom wax stamp, reminds him of the connection and encouragement that helped him succeed. But that success did not come easily. As Dexter begins his new role as Executive Director of the FRIENDS of Barack Obama Male Leadership Academy (BOMLA), he is drawing on the wisdom of mentors who saw his potential and highlighted his innate leadership gift.

Dexter at age three.

As a child growing up outside of Grand Rapids, Michigan, Dexter learned the value of relationships in unlikely places. He met his first mentor when he was just two months old. Diane was a white woman in her 30’s who eventually became Dexter’s godmother. “I grew up in a home where my mother was 16 years old when she was pregnant with me. She had me just a couple weeks after her 17th birthday. My father was around, but not in the home seeing that they were never married,” remembers Dexter. “My grandfather knew Diane from work and whenever he had a situation come up where he needed help and my mom was in school, he would go to Diane and say ‘I need you to watch my grandson.’”

The visits continued as Dexter’s mother, Joy, grew to become friends with Diane as well. Dexter spent many weekends with Diane, working on puzzles and writing thank you cards. The pair would even create construction paper letters to mail to Dexter’s mother when she moved overseas for a short time with her new husband, stationed with the US military in Germany. “One of the things that Diane told me often as a kid was, ‘you are special,’ and that helped me to be very confident in myself and who I was,” Dexter says. “There were a lot of people around me, my parents and other mentors who came into play later on in my life, who always pushed me and told me the door is wide open, I can go get it, even though I faced external barriers—I was young, Black, and poor. But I understood that leadership was something that I could own. If I couldn’t own anything else, I could own leadership.”

Dexter’s first experience with leadership came quickly. In middle school he ran for student council treasurer—and won. “My campaign slogan was ‘More Man for Your Money,” Dexter says with a laugh. Then at twelve years old Dexter took on his first job as a youth leader for an afterschool program. His younger siblings attended the program and his mom eventually took on the director role. “I was paid $50 every two weeks and I saved up for shoes,” Dexter says. “I knew having a job meant I had responsibilities and it was something I chose to do and wanted to do.”

Dexter’s middle school experience was also a lesson in facing challenges as an outsider. He was accepted to a predominantly white arts academy in 6th grade and traveled across county lines to attend each day. “I was really into the arts in general, but I was the token Black kid,” Dexter says. “My early experiences with visual arts gave me an understanding of who I was, but that led into the theater arts and dance—I was Charlie Brown in the Peanuts play in the 8th grade—and it was a challenge. I knew I looked and sounded different.” But those obvious differences, and even encounters with blatant racism, shaped who Dexter would become as a leader and mentor.

Starting his freshman year of high school, Dexter was back in his neighborhood, back with the friends he hadn’t seen since elementary school, and back with the identity as an “arts kid.” Dexter says, “I immediately told everyone that I was going to become drum major.” The school, Muskegon Heights, was nationally recognized for their marching band, and typically drum majors were seniors who had earned the honor, but Dexter was given the role his sophomore year, and continued as drum major until graduation. “This was a high-stepping, HBCU-style marching band and the band director was an institution within an institution, a well-known musician from Florida A&M University, leading this force of a band,” says Dexter. “I didn’t know they were watching me, but they were, and I was given the leadership mantle.” Dexter’s determination paid off, as the band won first place in almost every category of band competition, including drum major. And the band director, Robert Moore, became a guide for Dexter as he made decisions about his future.

But with a focus on band, Dexter saw his academics slip, graduating high school with his GPA under 3.0. And though he earned a band scholarship, the price tag at his college of choice, Hampton University, was still too steep for Dexter’s family. “I decided to attend a regional state school, Fair State University, but three weeks before classes started, they told me my financial aid didn’t pan out and I ended up at community college,” Dexter says. “It was a really interesting moment in my life. I felt like I had accomplished so much—the local paper had written about me, I had been working at the same nonprofit throughout middle and high school, other students looked up to me—how am I not doing all the things I wanted to do?”

Full of questions and lacking clear direction, Dexter went to visit a friend in Dallas. “I was supposed to stay for three days, but I stayed for two weeks,” Dexter remembers. He got to know Dallas through his friend, as she showed him around the city, including her school, Paul Quinn College. “I fell in love with the college, fell in love with a church, and fell in love with the city,” Dexter says. He immediately applied for school at Paul Quinn and got a job at a nearby gas station. “I told my mom I was moving to Dallas in January and started school at Paul Quinn at the beginning of 2008,” Dexter says.

>

“I fell in love with the college, fell in love with a church, and fell in love with the city.”

Six months earlier, Michael Sorrell had begun his tenure as president of Paul Quinn College, stepping into a sinking ship as the school had dropped from nearly 1,000 students to 150. Buildings were badly in need of maintenance, and morale was low across the campus. Both President Sorrell and Dexter needed a fresh start for Paul Quinn.

“I met the new admissions standards that Paul Quinn had put in place, and the financial aid package wasn’t pretty, but it was better than what I had before,” Dexter shares. “Between Pell grants and student loans, I was able to get started.” To keep his education funded, Dexter enlisted in the U.S. Army Reserves, and served in nutrition care at the Seagoville base, about fifteen miles away from Paul Quinn. “I needed to pay for school, but I also needed some discipline, so I enlisted before I even told my parents, and then promised them I wouldn’t go overseas,” Dexter says.

Dexter leading a rally for justice after the 2012 death of Trayvon Martin.

With a newfound focus, Dexter poured himself into life at Paul Quinn, joining the cross country team, earning an All-American title, and starting a journey into student government. During his freshman year, he served as a campus representative. As a sophomore he was elected chaplain, and then as a junior, he won his bid for student body president. “It was a really interesting time for Paul Quinn, we almost lost everything, and I was one of the students that President Sorrell called and said ‘I need you to have faith. Believe that things are gonna be okay and we’re gonna come out on the other side,’” Dexter remembers. “And I had one application open for UTA and another for Jarvis Christian College. But I never pushed submit on either of them because I had seen the relationships that were built at Paul Quinn and the strides we had taken, and I knew we were going to be ok.”

As Dexter’s leadership skills transformed, Paul Quinn transformed around him. And President Sorrell let Dexter know that he was part of that transformation, encouraging him to step into social justice issues in the surrounding community and show what the Quinnite Nation was capable of accomplishing.

One of the largest campaigns Dexter led was a movement called We Are Not Trash, fighting against the city’s decision to re-route all Dallas garbage to the McCommas Bluff Landfill, greatly expanding the landfill footprint in a southern Dallas residential area, just two miles from Paul Quinn. After the Dallas city council voted to allow the landfill expansion, Dexter helped lead a march of 700 people from Oak Cliff to city hall to gather awareness. Several months later, on Dexter’s birthday, a federal judge blocked the city’s decision and the expansion was not permitted to proceed. “That ruling solidified everything I hoped for when I decided to be a part of a leadership initiative,” Dexter says.

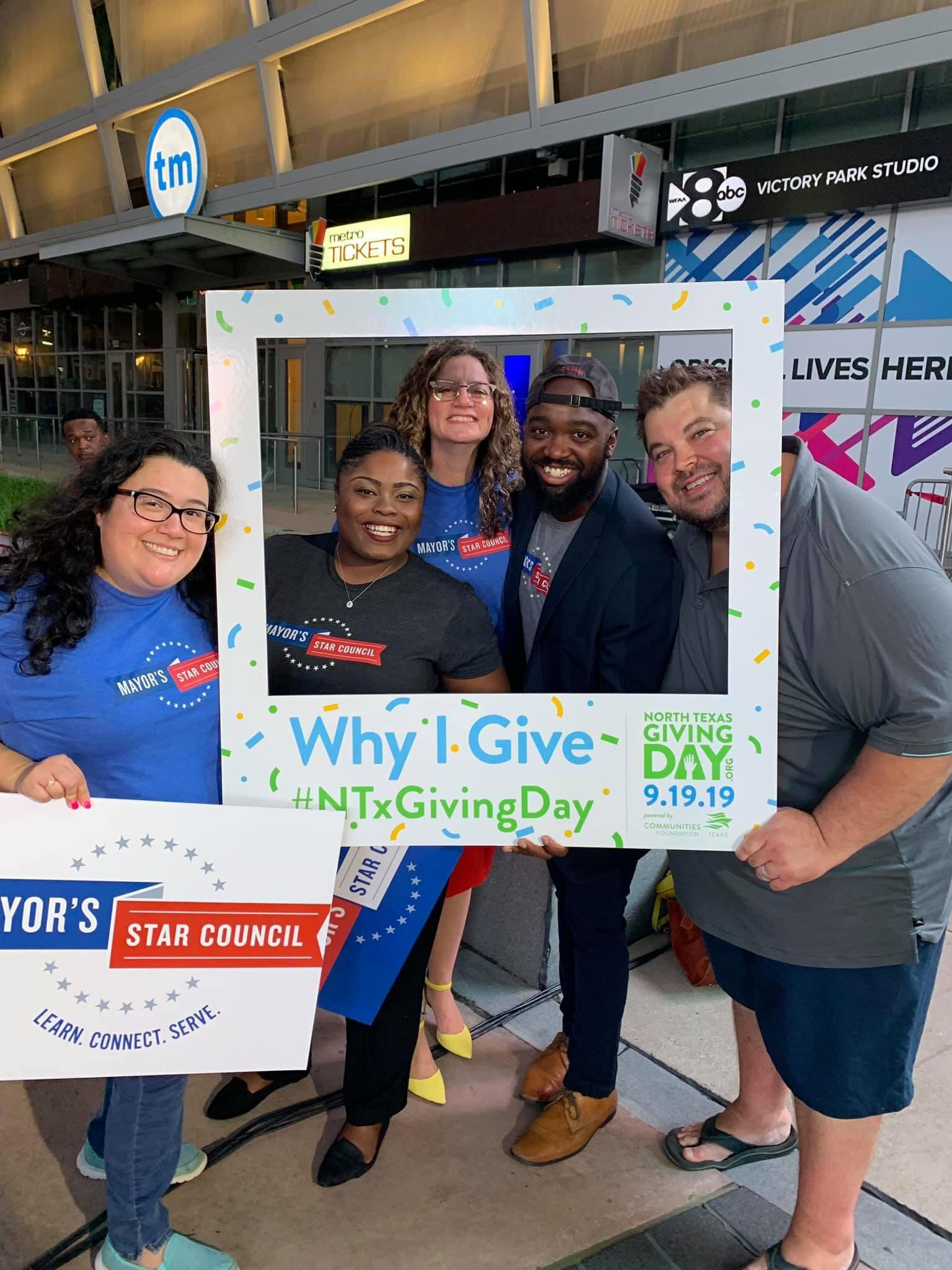

Dexter leading the fundraising team for the Mayor’s Star Council for North Texas Giving Day.

After graduation and an internship at Big Thought, Dexter considered continuing his higher education in Urban Planning, but ended up taking a job in Dallas. A few months later, he got another call from Michael Sorrell, offering Dexter a new position at Paul Quinn—Civic Engagement Coordinator. “That job helped me to understand the position that Dallas has on social mobility for marginalized communities. It was my sole purpose to plug Paul Quinn into what was happening with the city, and I saw how my leadership and service could truly make a difference for the students at Paul Quinn,” Dexter says. That leadership eventually led to a spot on the Mayor’s Star Council, and a connection with a growing network of movers and shakers across North Texas.

With new staffing, partnerships, and priorities in place, Paul Quinn began to thrive again, transitioning into a nationally recognized urban work college. Michael Sorrell also began his doctoral program at the University of Pennsylvania and leaned on Dexter to keep progress moving forward on campus. “President Sorrell told me, ‘There is nobody who knows our culture like you do. I need you here to help hold down what we have built over the past six years,’” Dexter remembers. “Typically you lean into your mentor, but as a mentor, he leaned into me. And as a young man, that felt promising. I had an important role to play to ensure the livelihood of Paul Quinn.”

In 2017, Dexter followed in Michael Sorrell’s footsteps, heading to University of Pennsylvania for a year-long masters degree and certificate program in Higher Education and Africana Studies, while serving as an international philanthropy fellow at the Wharton School. “I lived in one of the poorest neighborhoods in the US right next to this elite school, and took a course in the psychology and education of black males—how to work with black men from preconception to adulthood,” Dexter says. “But that course was introspective and reflective for me. I had to face my own underlying issues with my paternal relationship, self-image, and post traumatic stress from growing up in poverty. I’m grateful the professor and co-professor really took care of the students in that class, but I dealt with a dark depression for about three weeks.” Dexter also experienced his work with Paul Quinn being highlighted in various classes on current approaches to urban education and was able to share first-hand knowledge with his fellow classmates.

Dexter at his graduation ceremony for the University of Pennsylvania.

When Dexter returned to Paul Quinn after graduating from Penn, he stepped into a new job on campus—Special Assistant to the President. “I felt ready; prepared for this new role,” Dexter says. “This job was a deep dive into nonprofit development and cultivating relationships.” But within a year Dexter was promoted to Associate Dean of Student & Alumni Affairs, bringing his direct work with students full circle. Dexter says, “I was building campus culture through students and alumni, building community through engagement between student participation and alumni giving.” His growth as a trailblazer was translating directly into the growth of the college that had allowed him the opportunity to lead.

At the end of 2020, a colleague of Dexter’s told him that the FRIENDS of Barack Obama Male Leadership Academy (BOMLA) was looking for a new Executive Director and thought he would be a perfect fit. Dexter applied for the role and was hired at the start of 2021, ready to lead the ten-year-old nonprofit that supports the Dallas ISD magnet school. The FRIENDS of BOMLA is celebrating ten years of fundraising and friendraising for student, program and professional enrichment opportunities. Due to public education’s financial realities, community support for public schools has become vital. With its independent board of directors, FRIENDS of BOMLA is working to close the funding gap between available school district funding and the ambitious and creative opportunities that students need and deserve. For Dexter, this new challenge is an extension of not only his career, but his life experience. “BOMLA is building better brothers, husbands, fathers, and leaders for our communities,” Dexter says. “It is important that our young men have someone who has lived their experience step forward to share their stories with donors and philanthropists. My lived experience prepared me for this post.”

Dexter D. Evans in January 2021.

Even in the complicated days, weeks, and months of COVID, Dexter is determined to keep showing up for his new community, popping into classrooms and Zoom meetings, getting to know the students, teachers, and administrators that create the BOMLA culture. “From my years at Paul Quinn, I feel comfortable fundraising and connecting with our students. When I look at these Black and Brown boys who are aspiring leaders, I can see that they want to be all the things in the world, and that’s exactly who I was, and who I am now. They don’t have to work hard to connect with me as a resource, guide, or mentor,” Dexter says.

That first phone call from Michael Sorrell still shapes how Dexter views mentoring. “I didn’t know President Sorrell well, but he reached out. He opened the door that I didn’t know needed to be opened. It was an opening of trust for the two of us,” Dexter says. “It has always been back and forth, and even when I told President Sorrell about this new opportunity he told me what a great leadership step it would be. He was thrilled. He was proud of me and saw my success as a Paul Quinn success.” With that trust and belief ringing loud and clear, Dexter is honed in on connection and love for something greater than yourself—encouraging a new generation to lead with boldness.

If you would like to learn more about the FRIENDS of BOMLA please visit bomlafriends.org.

More Good Stories

Featured

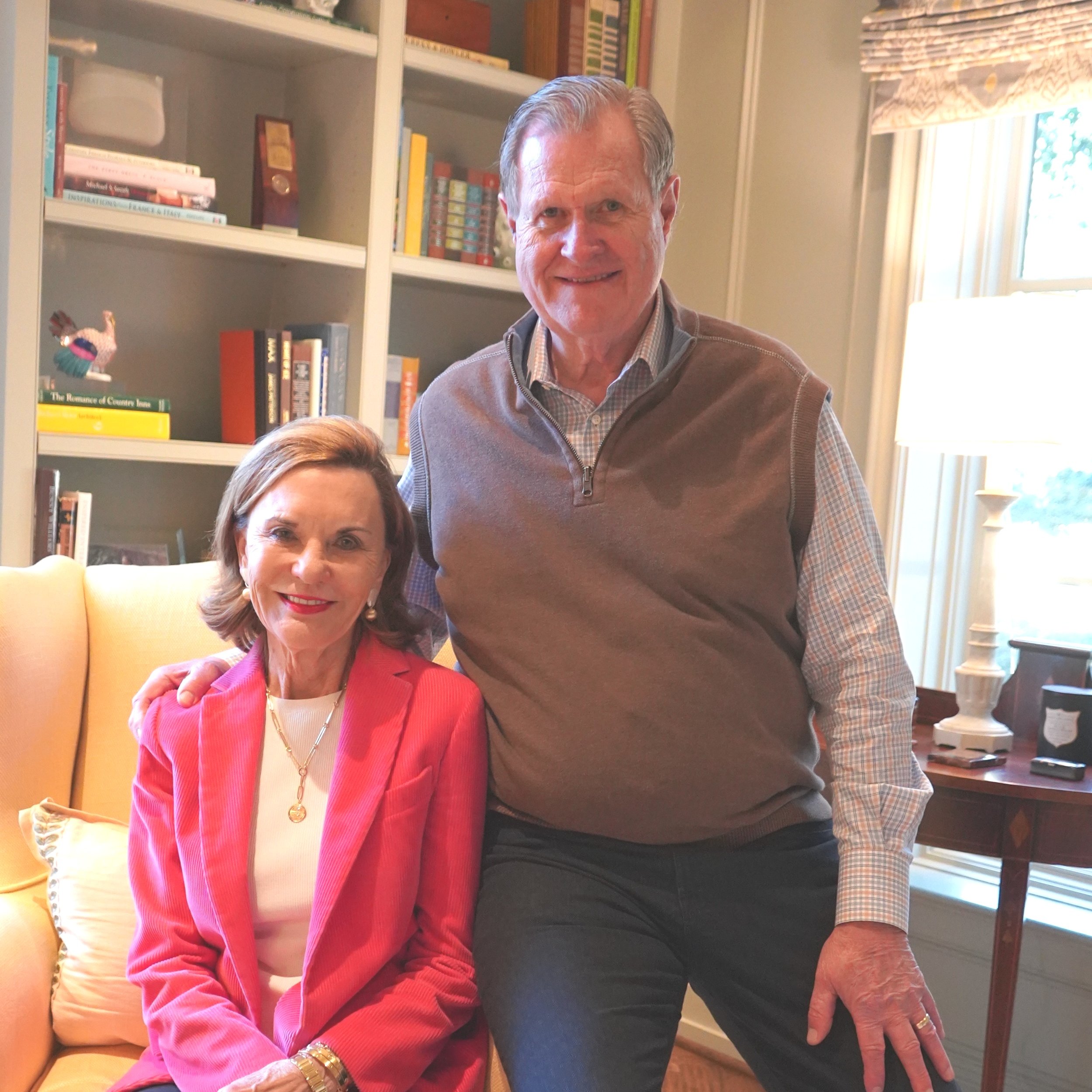

When Kathy and Larry Helm heard about The Senior Source’s 60th Birthday Diamond Dance-Off, they knew they had to put on their dancing shoes! For the Helms, this event combined two of their passions into one. Celebrating and supporting The Senior Source, a Dallas-area nonprofit that has been serving older adults for 60 years, and dancing together, which they have been doing since they were high school sweethearts. Both Kathy and Larry have chaired the board of directors of The Senior Source and have been proud supporters since 1998. It seemed only fitting they should be voted into the finals to dance on stage at Klyde Warren Park this past summer.

In 2020, more than 912,000 women were diagnosed with some form of cancer in the United States alone. During that same pandemic year, countless medical appointments were canceled while people were social distancing, and yet still each day nearly 2,500 women heard the news, “you have cancer.” There is no doubt that these words can be crushing to hear, but what’s equally crushing is the lack of tangible, encouraging support that exists to help women feel beautiful, strong or “normal” before, during and after cancer treatment.

When Tom Landis opened the doors to Howdy Homemade in 2015, he didn’t have a business plan. He had a people plan. And by creating a space where teens and adults with disabilities can find meaningful employment, he is impacting lives throughout our community and challenging business leaders to become more inclusive in their hiring practices.

Have you ever met someone with great energy and just inspired you to be a better you? Nitashia Johnson is a creator who believes by showing the love and beauty in the world it will be contagious and make an impact. She is an encourager and knows what “never give up” means. Nitashia is a multimedia artist who works in photography, video, visual arts and graphic design. Her spirit for art and teaching is abundant and the city of Dallas is fortunate to have her in the community.

The United Nations Association Dallas Chapter (DUNA) honored Rev. Bill and Norma Matthews for their ongoing commitment, helping advance the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals agenda by promoting peace and well-being.