Published July 30, 2018 at 10:54am.

Story and photos by Hunter Lacey.

While Stephanie Giddens was a student at Texas A&M University, she spent several weeks in India. That singular trip changed her worldview dramatically. She struggled to reconcile that simply by birth, she had access to clean water, clean air, safety, and education while a fellow human born in a slum in Calcutta had no access to any of those things. “Just seeing that, I realized, ‘okay, maybe my money and time isn’t meant for just me. Maybe it’s meant to do something good and help bridge this gap,’” Stephanie said. “How can I use what I have been given to help the person who hasn’t been given?”

Following her graduation from Texas A&M, Stephanie attended and graduated from Dallas Theological Seminary with a master’s in theology. She began working in women’s ministry soon after, launching the organization “Polish,” now known as “Polished.” Polished has bettered the lives of women both in Dallas and Rwanda by partnering businesswomen in Dallas with like-minded women in Rwanda. In 2011, Polished fundraised to train Rwandan women in microfinance to start their own businesses and held a panel to educate people in Dallas on the realities of human trafficking.

Because Stephanie held a front-row seat to these projects, she made a point to study up on the marginalization of women. “That was the turning point,” she remembered, “I always had a concern for the marginalized, but these two projects were kind of the turning point when I realized my whole life was about to jump track. I wanted to really dig in to helping women who had not been afforded things like education.”

Women empowerment soon became central to Stephanie’s heart. As a result of her work with Rwandan women through Polished, Stephanie and her husband felt an intense desire to move to Rwanda. “My husband got a job with an American consulting firm over there. We were going to learn the business environment, learn the culture for two or three years, then start our own social business endeavor. And 24 hours before we shipped our container overseas, the job fell through. So we didn’t move. It was bad. It was really expensive, and it was a big mess,” Stephanie said.

For both Stephanie and her husband, the confusion of this sudden change was difficult to handle. “It probably took about two years for the dust to settle and for us to recover – or start recovering – financially, emotionally, mentally, all of that,” she said. Though Rwanda was no longer possible, Stephanie’s heart was in the same place. Opportunity for marginalized women. “My church started getting involved with refugees here in the Vickery Meadow neighborhood, and I realized – with the nudging of some friends because I still wanted to go to Africa – there are people that need just as much help who live five minutes from me here in Dallas. Why don’t we do it here?”

The refugees in Dallas, like in many cities, are typically under-resourced and undereducated. “What can I do to help in that situation?” Stephanie asked. “I built a company that would accommodate for those things – where they could have a lower English proficiency and lower job skills,” she said. Production seemed like the way to go, and after looking at the market for fair-trade goods, children’s clothes seemed to be a missing piece. “There are tons of great companies doing jewelry and accessories and things like that, and I want to continue to support them and not compete with them,” she said.

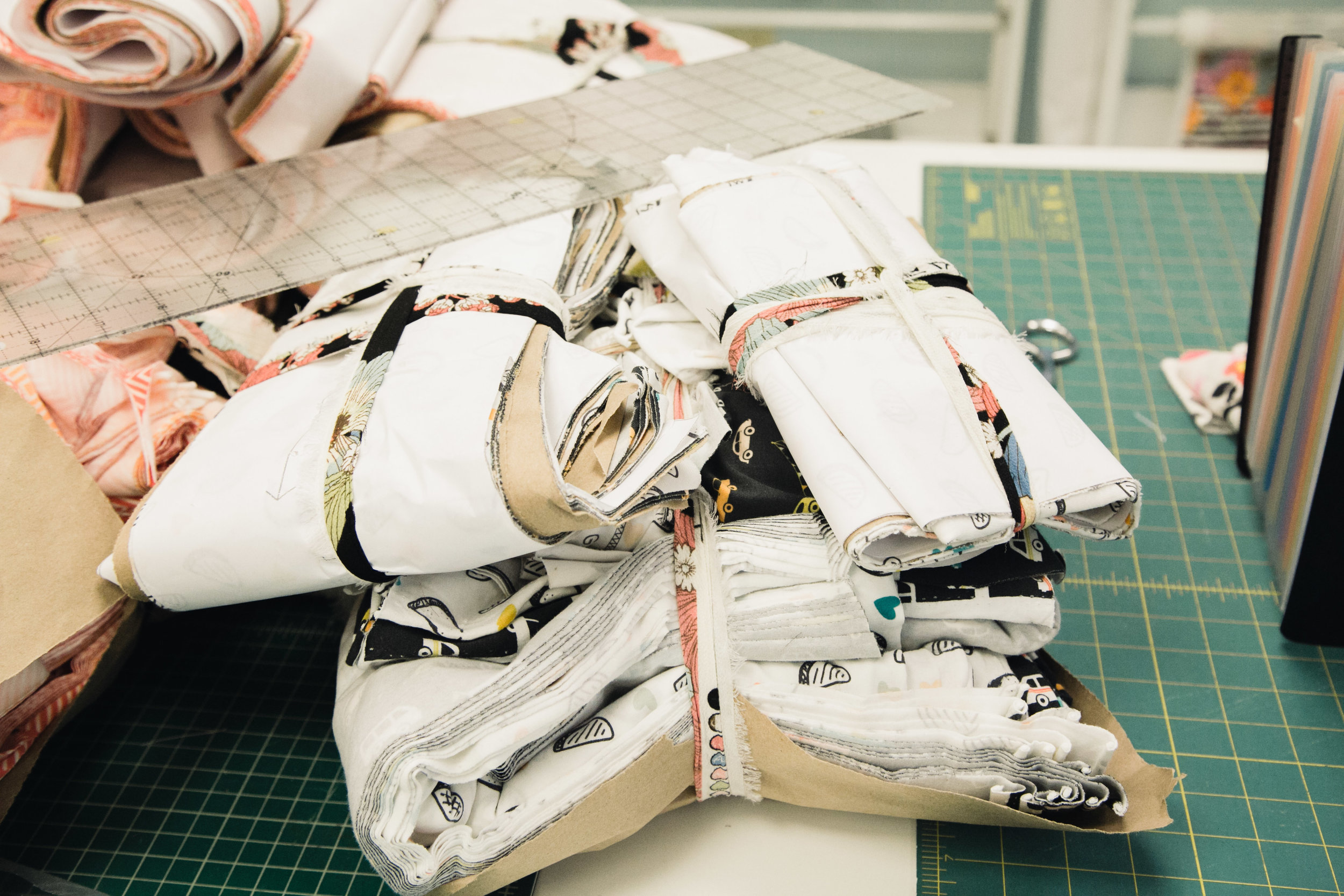

With no background in fashion or retail but eager to use that industry as an avenue toward aiding refugees in their adjustment to life in the states, Stephanie took sewing lessons and began product creation. She held focus groups to learn what moms want in clothes for their kids. It became clear early on that the fabric and the labor would be expensive, making the clothes an inevitably high price. “I wanted to make sure we could create something that’s cute enough to validate this price point,” she said. “Ultimately, though, the cost of the garments goes back to the women in their paycheck, because they are making fair wages.”

Vickery Trading Company incorporated as a non-profit in 2015, and launched production in June of 2016. When the program began, they outfitted a space in the Northwest Community Center in Dallas to be the production center. Of the four walls surrounding the space, two are completely transparent windows. “From the beginning, I wanted it to be abundantly clear that we are not a sweatshop. Having this whole glass wall, we are completely visible to the world, and people can see that this is a bright, happy, shiny place. They can see just what’s going on, see how well the women are loved,” Stephanie shared.

Because the program is not just about production of clothes, Vickery Trading Company was constantly outsourcing learning opportunities. “We always had English Second Language (ESL) and reading, but we had a doctor coming in and doing women’s health, and counselors coming in and doing mental health, and the fire department coming out and teaching us about fire safety. All of this was great and wonderful and needed, but not all of it really helped prepare refugees for employment,” Stephanie said. After further evaluating the goal of Vickery Trading Company, they shifted to focusing solely on what gets each woman most prepared to be an employable community member. From there, the focus became speaking, reading, and writing English, as well as typing classes to keep them comfortable with technology. Recently, Vickery Trading Company graduated its first five women. These five are respectively transitioning into new jobs, starting their own business, or going on to take college courses.

Stephanie recalled, “people had told me when we were getting started, ‘you’re never going to be able to get a woman from Iraq and a woman from Afghanistan to work together,’ and I was like, ‘oh, really? Well, watch me.’” Sure enough, when work began, women would ask to be seated apart from certain women. Stephanie would always say no. She would pair them off to work together randomly. For instance, “okay, you’re both wearing red,” she’d say. In reality, she’d intentionally choose people who weren’t speaking to one another. One of the ways they learned English was by having organized time to speak to one another in English. Stephanie would throw out a neutral question like, “what’s your favorite food from home that you miss?” and the women would get to know each other through this time.

“Slowly, after about 3 weeks, you started to see all these walls come down. They were playing with each other’s hair, laughing together at lunch. We started to see this family form, and since then it’s really become this sweet little community,” Stephanie shared. “They’ve realized together that we all have a lot more in common that we have different from one another.” These women are now teammates. They hang out together on the weekends, they take each other food when they’re sick, they’re each other’s support system. They speak English to one another and as a result, they’ve grown more confident in their ability to navigate day-to-day life in the states. Each woman that goes through the program will someday go on to a higher level job or to continue her education. Because of Vickery Trading Company, they will have the life skills to thrive in the United States.

In Vickery Meadows, just a few minutes from Lake Highlands, there are around 20,000 refugees. “That’s what changed my heart: paying attention to what’s going on. I got outside of what’s going on in my little world here in Dallas and paid attention to what was going on in the world. And then came back, and realized it’s happening right here in front of my face,” Stephanie shared. “How can I not do something?”

There are multiple ways to volunteer at Vickery Trading Company if you’d like to get involved. You can see those opportunities here. You can also support them by checking out their online store or visiting them in person to make a purchase.

If you know someone who is Doing Good in Dallas, we’d love to hear about it! Share their story with us.

Story and photos by Hunter Lacey.