Story by Nancy McGuire and Jennie Trejo. Photos provided by Southern Methodist University.

Dr. Barbara Minsker’s motivation has always been for her research to make a real difference in the world, not just be some academic paper and tools on a shelf. The study she published last year does exactly that– it could lead to massive improvements for Dallas residents currently living in “infrastructure deserts.”

Dr. Minsker first encountered Dallas in her move from Champagne, Illinois. She is currently the Bobby B. Lyle Professor of Leadership and Global Entrepreneurship Senior Fellow in the Hunt Institute for Engineering and Humanity at Southern Methodist University, but she says she took the job because, according to her, there would be a “very rich source of real-world issues for her research here.”

“The real driver for this particular work was when Cyndy Lutz took me on a tour of low-income neighborhoods in Dallas,” Dr. Minkser says. At the time, Cyndy had been working at Habitat for Humanity. She shared with Dr. Minsker the difficulties they faced related to building housing for residents when the infrastructure was not there.

It did not take Dr. Minsker long to notice a great disparity between different neighborhoods in Dallas when it came to basic infrastructure and the ensuing quality of life for the residents. The Habitat tour was the genesis of her application to study the infrastructure matter in more detail.

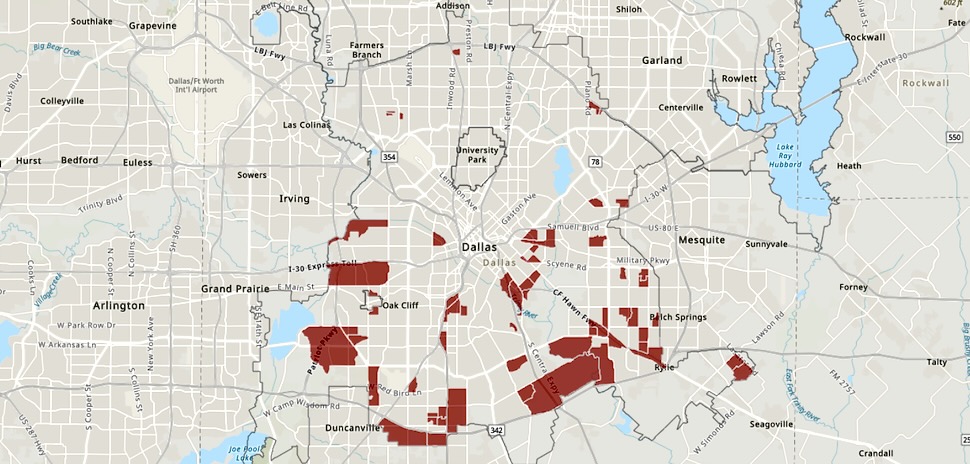

The study became a five-year project, supported by a $584,000 grant from the National Science Foundation. Dr. Minsker’s research team was comprised of one Ph.D. student, Zheng Li, and approximately 20 undergraduate engineering students. Together, they have identified 62 infrastructure deserts. These areas are “highly deficient” for infrastructure needed to maintain the quality of life all residents deserve.

“The main question we went in asking was, ‘What makes a neighborhood safe, livable, and viable?’” Dr. Minsker reflects. The variables they considered include the condition of streets and sidewalks, internet access, crosswalks, noise walls, street tree canopy, public transportation access, hospital or medical service access, bike and pedestrian trails, community gathering places, and food access.

The other research question they had was: Is neighborhood infrastructure equitable across neighborhoods with differing income and race/ethnicity?

Dr. Minsker and her team analyzed these variables in more than 800 Dallas neighborhoods. They also used household income statistics and ethnicity information, census-block data, sophisticated open-source data management software, and in-person “boots on the ground” assessments. Dr. Minsker’s team compiled the findings and created a rating system that ranged from “excellent” to “highly deficient.” You can see maps that break down the Dallas Infrastructure Conditions here.

Southern Dallas is home to most of the infrastructure deserts identified through the research process. It is home primarily to low-income Black and Hispanic/Latinx residents. The findings broadly demonstrate the growing inequity between the residents found north and south of I-30 regarding economic development, housing stock, and neighborhood services.

Dr. Minsker and her team studied other cities, including Chicago, Los Angeles, and New York City. They all have fewer infrastructure deserts than Dallas– and more equity between their neighborhoods.

“It’s a quality-of-life issue,” Dr. Minsker says. “We need to understand the generational effects of growing up in these conditions and the long-term negative impacts.”

Two of the most significant reasons these inequities matter have to do with safety and health. Intersections with highly deficient infrastructure, which could look like missing crosswalks or lights that do not work properly, are three times more likely to have pedestrian and bike accidents with cars. Aside from proximity to hospitals and other forms of healthcare, the Texas Trees Foundation found that there will be a 20 percent reduction in residential deaths by planting trees in the hottest areas and providing a source of shade.

How will the data be used now that Dallas’s infrastructure deserts are pinpointed? How will the inequities be addressed?

City staffers, council representatives, and Mayor Johnson have all seen the findings. They all have acknowledged that the study reemphasizes that areas of Southern Dallas have been deficient in development for a very long time, resulting from years of historical redlining and neglect.

Areas with basic infrastructure tend to draw more developers because that quality can help make projects more economically viable. Because of that, incentives for investment in neighborhood infrastructure are paramount to attract more development in the city’s southern sector.

Thankfully, that is already happening– on Jan. 25, 2023, the City Council unanimously approved and amended the City of Dallas Economic Development Policy and approved a new Economic Development Incentive Policy– both of which cite Dr. Minsker’s study.

“We are already seeing influence in the City of Dallas policy, which is very exciting,” Dr. Minsker says. “I’ve never seen that happen in my 26-year career.”

Additionally, several other City of Dallas department directors have indicated to Dr. Minsker that they would be interested in partnering on proposals that may lead to various streams of funding to address these urban infrastructure deserts. Nonprofits have also used the information provided by the study to understand how they can better allocate their efforts and resources.

While there is still work to be done, it is clear that Dr. Minsker’s study will not be collecting dust on the shelf anytime soon. You can look at the research team’s public website to dive deeper into the findings.

Sign up with your email address to receive good stories, events, and volunteer opportunities in your inbox.